T-I

Goal: understanding the energy landscape of the simplest spin-glass model, the Random Energy Model (REM).

Techniques: probability theory.

Large-N disordered systems: a probabilistic dictionary

- Notation. We will discuss disordered systems with degrees of freedom (for instance, for a spin system on a lattice of size in dimension , ). The disorder can have various sources: (e.g., the interactions between the degrees of freedom are random). Since the systems are random, the quantities that describe their properties (the free energy, the number of configurations of the system that satisfy a certain property, the magnetization etc) are also random variables, with a distribution. In this discussion we denote these random variables generically with (where the subscript denotes the number of degrees of freedom) and with their distribution. We denote with the average over the disorder (equivalently, over the distribution of the quantity, induced by the disorder). Statistical physics goal is to characterize the behavior of these quantities in the limit . In statistical physics, in general one deals with exponentially scaling quantities:

- Typical and rare. The typical value of a random variable is the value at which its distribution peaks (it is the most probable value). Values at the tails of the distribution, where the probability density does not peak but it is small (for instance, vanishing with ) are said to be rare. In general, average and typical value of a random variable may not coincide: this happens when the average is dominated by values of the random variable that lie in the tail of the distribution and are rare, associated to a small probability of occurrence.

Short exercise.Consider a random variable with a log-normal distribution, meaning that where is a random variable with a Gaussian distribution with average and variance . Show that while , and thus the average value is larger than the typical one. - Self-averagingness. The physics of disordered systems is described by quantities that are distributed when is finite: they take different values from sample to sample of the system, where a sample corresponds to one "realization" of the disorder. However, for relevant quantities sample to sample fluctuations are suppressed when . These quantities are said to be self-averaging . A random variable is self-averaging when, in the limit , its distribution concentrates around the average, collapsing to a deterministic value: This happens when its fluctuations are small compared to the average, meaning that [*] For self-averaging quantities, in the limit the distribution collapses to a single value , that is both the limit of the average and typical value of the quantity: sample-to-sample fluctuations are suppressed when is large. When the random variable is not self-averaging, it remains distributed in the limit .

- Quenched averages. Consider exponentially scaling quantities like , that occur very naturally in statistical physics. How to get from ? On one hand, if we know how to compute , then: If is self-averaging, we can also use In the language of disordered systems, computing the typical value of through the average of its logarithm corresponds to performing a quenched average: from this average, one extracts the correct asymptotic value of the self-averaging quantity .

- Annealed averages. The quenched average does not necessarily coincide with the annealed average, defined as: In fact, it always holds because of the concavity of the logarithm. When the inequality is strict and quenched and annealed averages are not the same, it means that is not self-averaging, and its average value is exponentially larger than the typical value (because the average is dominated by rare events). In this case, to get the correct limit of the self-averaging quantity one has to perform the quenched average.[**] This is what happens in many cases in disordered systems, for example in glassy phases. Sometimes, computing quenched averages requires ad hoc techniques (e.g., replica tricks).

Example 1. Consider the partition function of a disordered system at inverse temperature , . When is large this random variable has an exponential scaling, , where the variable is the free energy density. This scaling means that the random variable remains of when , and we can define its distribution in this limit. In all the disordered systems models we will consider in these lectures, the free-energy not only has a well defined distribution in the limit, but it is also self-averaging: it does not fluctuate from sample to sample when is large, and similarly for all the thermodynamics observables, that can be obtained taking derivatives of the free energy. The physics of the system does not depend on the particular sample.

Example 2. While intensive quantities like are self-averaging, quantities scaling exponentially like the partition function are not necessarily so: in particular, we will see that they are not when the system is in a glassy phase. Another example is given in Problem 1 below, where and .

- [*] - See here for a note on the equivalence of these two criteria.

- [**] - Notice that the opposite is not true: one can have situations in which the partition function is not self-averaging, but still the quenched free energy coincides with the annealed one.

Problems

This problem and the one of next week deal with the Random Energy Model (REM). The REM has been introduced in [1] . In the REM the system can take configurations with . To each configuration is assigned a random energy . The random energies are independent, taken from a Gaussian distribution

Problem 1: the energy landscape of the REM

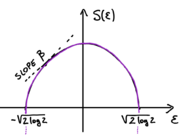

In this problem we study the random variable , that is the number of configurations having energy . For large this variable scales exponentially . Let . The goal of this Problem is to show that the asymptotic value of the entropy , that is self-averaging, is given by (henceforth, ):

- Averages: the annealed entropy. We begin by computing the annealed entropy , which is defined by the average . Compute this function using the representation [with if and otherwise].

- Self-averaging. For the quantity is self-averaging: its distribution concentrates around the average value when . Show this by computing the second moment . Deduce that when . This property of being self-averaging is no longer true in the region where the annealed entropy is negative: why does one expect fluctuations to be relevant in this region?

- Rare events. For the annealed entropy is negative: the average number of configurations with those energy densities is exponentially small in . This implies that the probability to get configurations with those energy is exponentially small in : these configurations are rare. Do you have an idea of how to show this, using the expression for What is the typical value of in this region? Putting everything together, derive the form of the typical value of the entropy density.

- The energy landscape. When is large, if one extract one configuration at random (with a uniform measure over all configurations), what will be its energy? What is the equilibrium energy density of the system at infinite temperature? What is the typical value of the ground state energy? Deduce this from the entropy calculation: is this consistent with Alberto's lecture?

Check out: key concepts

Self-averaging, average value vs typical value, rare events, quenched vs annealed.

To know more

- Derrida. Random-energy model: limit of a family of disordered models [1]

- A note on terminology:

The terms “quenched” and “annealed” come from metallurgy and refer to the procedure in which you cool a very hot piece of metal: a system is quenched if it is cooled very rapidly (istantaneously changing its environment by putting it into cold water, for instance) and has to adjusts to this new fixed environment; annealed if it is cooled slowly, kept in (quasi)equilibrium with its changing environment at all times. Think now at how you compute the free energy of a disordered system, and at disorder as the environment. In the quenched protocol, you first compute the average over the configurations of the system (with the Boltzmann weight) keeping the disorder (environment) fixed, so the configurations have to adjust to the given disorder. Then you take the log and only afterwards average over the randomness (not even needed, at large , if the free-energy is self-averaging). In the annealed protocol instead, the disorder (environment) and the configurations are treated on the same footing and adjust to each others, you average over both simultaneously. The quenched case corresponds to equilibrating at fixed disorder, and it is justified when there is a separation of timescales and the disorder evolved much slower than the variables; the annealed one to considering the disorder as a dynamical variable, that co-evolves with the variables.